Jun 17, 2025

Building and Managing a Cultural Plant Propagation Centre

When it comes to nursery planning for a Cultural Plant Propagation Centre, every location is a unique story, shaped by its soil, water sources, community priorities, and the unpredictable realities that emerge once you actually begin to bring all the pieces together.My experience over the last decade has brought me to this understanding - no matter how carefully I mapped out a budget or drew up a timeline, no matter what the parameters of the project funding said, the reality of the real situation on the ground always found a way to surprise me. Effective community engagement not only mitigates risk, it is the foundational element of developing a sustainable plant nursery project. This process of drawing on the expertise of community members, botanists, rangers and our team of nursery managers honours and reflects the amazing diversity of experience available. Each community has brought a different perspective, shaped by their land, culture, climate and needs.It All Begins with Community EngagementEvery site begins with a community engagement. This isn’t just a box to check; it’s a fundamental process that reveals the deeper potentials of your greenhouse project. It can be the difference between long-term sustainable success, and failure. What works for one nursery—say, a focus on mine site restoration—may be irrelevant for another, where bush food and cultural plants like lemongrass or acacia are the priority. Engaging with community stakeholders, from elders to local schools and any land and sea rangers in the region, is not just best practice—it’s essential for understanding what your nursery should become.The importance of Site SelectionSite selection is where environmental and community considerations take centre stage: this is about having reliable access to quality water. But that’s just the beginning. sunshine, community considerations, energy reliability, land availability, land council zoning, and microclimate all play crucial roles. Surprises are inevitable—sometimes a site that looks perfect on paper reveals hidden challenges, like unexpected restrictions from a land council or deeper issues within the community.Start at a Managable ScaleOne of the best pieces of advice is to start with a smaller scale nursery. This is a risk mitigation strategy, but it’s also a reality check. My first nursery in Tennant Creek, NT taught me that developing cost estimates is never as simple as it seems. Labor, outreach, infrastructure, and even small supplies add up quickly. It is also vital to factor in the costs of community engagement - cultural advice and education are often overlooked, but critically important for long-term success.See What other Communities are DoingVisiting other nurseries has been invaluable. Some thrive on volunteer energy, with a flexible, community-driven approach. Others run like small-scale businesses, with strict protocols and detailed work plans. Both models have their strengths, and seeing them in action has helped me refine the best practices we use at Bush Botanics. Adapting strategies from a range of nurseries leads to better outcomes, especially when combined with ongoing feedback and adaptation - see what is already working, and why.Ultimately, building and managing a Cultural Plant Propagation Centre is about embracing unpredictability and engaging the entire community. Strategic planning, detailed cost estimation, and a willingness to learn from both mistakes and successes—these are the real foundations of a resilient and sustainable nursery project. Begin With the End in MindWhen I first started building plant nurseries in remote communities, it was mostly about bush foods and botanicals. Having evolved this process into the ecological restoration sector, it has fundamentally changed how I approach cultural plant propagation and nursery management. The philosophy is simple, but its impact is profound: start at the outplanting site, not in the greenhouse. This means every decision—from species selection to propagation protocol—flows from the needs of the land and the people who will steward it. You can’t separate the plant from its purpose, or the nursery from its people. Knowing what and where you are going with the plants is a key distinction that will inform the entire process.In practice, this approach turns nursery work into a living feedback loop. It’s not just about growing plants; it’s about growing the right plants, for the right place, at the right time. The starting with the end in mind approach is built on six sequential steps, each designed to ensure that every plant leaving the nursery is set up for success in its new home: Define project objectives: Whether it’s ecological restoration, using traditional food varieties like acacias and lemongrass, or planting hardwoods for boomerangs and cultural harvest, clear goals come first.Choose the best plant material: Seeds, root stock, cuttings, bareroot, or container seedlings—each has its place, depending on the site and purpose.Ensure genetic diversity: Research shows that maintaining genetic diversity is crucial for resilient plant populations. This means sourcing from a broad range of donor plants and matching seed zones to outplanting sites.Identify site limiting factors: Water, soil, temperature, winds, erosion—these can make or break outplanting success. Each site tells its own story.Select the optimal planting window: Timing matters. While spring is traditional, autumn or even summer plantings may be best, especially with specially conditioned stock.Pick the right tools and process: From bobcats and augers to cultivators and wheelbarrows, the method must fit both ecological and practical needs.What surprised me most was how this approach deepened my understanding of culturally important plants. For many indigenous nurseries, the goal isn’t just ecological restoration—it’s cultural renewal. Plants like saltbush, lemon myrtle (Backhousia citriodora) and Bush tomato (Solanum centrale) aren’t just species on a list; they’re woven into traditions, livelihoods, and identities. Outplanting for these priorities adds layers of meaning and complexity that go far beyond standard nursery practice. Plus accessibility to the harvest areas is crucial.Another lesson: genetic diversity and seed zones are worth exploring (more on this in future posts). Studies indicate that matching plant genetics to local conditions is essential, especially for long-term resilience.Ultimately, this approach of designing the nursery based on what and where the plants are going to end up is a philosophy rooted in collaboration. It asks nursery managers to listen—to the land, to their clients, and to the community members they serve. It’s a reminder that cultural plant propagation is as much about people and place as it is about plants themselves.Learning as You GoIf there’s one truth I’ve learned from years in nursery management, it’s this: even the best training is no guarantee of long-term success. Every season brings its own surprises. One year, a late frost might threaten young seedlings; the next, a rogue camel invasion can undo weeks of careful planning. These aren’t just inconveniences—they’re reminders that best practices must be flexible. Research shows that outplanting success depends on more than just following protocols. Soil conditions, seed quality, plant selection, and adaptability all play a role. Sometimes, despite our best efforts, we only know if we got it right after several years—and a few failures—have passed. Stay resilient!That’s why ongoing evaluation is at the heart of effective nursery management. Bush Botanics has been working with our community partners in monitoring outplanting results for over many years now - and we are just getting started. This long feedback loop is essential. It’s not enough to see plants in the greenhouse looking healthy; true success is measured by their survival and growth in the field. Community engagement is also critical. I’ve found that regular outreach and engagement—whether through educational events, informal visits and conversations, or structured feedback—shapes our routines in unexpected ways. Our ongoing staff training evolves as we learn from both our own experiences and the wisdom of elders, instructors, land and sea rangers and community members. Our advisory services and hands-on support empowers teams to respond to new challenges, and provides time and support for experimentation into the overall project schedule. This is an important part of the process. I’ve learned to see the planning process as ongoing. It’s not a one-time event, but a cycle of revisiting the vision, assessing progress, trying new things and adjusting to new realities. Sometimes, the most valuable insights come from unexpected places—a elder’s observation, student feedback, or the results of a small pilot project. These moments remind me that nursery management is as much about listening and learning as it is about growing plants.In the end, the path to growing a successful cultural plant project is rarely straightforward. It’s shaped by the land, the community, and the willingness to adapt. Our Nursery Management Course can provide a foundation, but it’s our working together as a collective experience, building capacity and resilience, and a lifelong commitment to best practices that truly sustain a native plant nursery. The journey is long, sometimes uncertain, but always rooted in collaboration, growth and community aspirations.Running a successful on-country cultural plant nursery—particularly in remote communities—demands creative teamwork, localized strategies, and the humility to adapt and learn.The rewards?Plants that heal ecosystems, cultural revitalization, and communities coming together in learning and celebration.If the Bush Botanics team can help you plan, fund, build or manage your native plant nursery, please contact us at william @ bushbotanics.com.

8 Minutes Read

Jun 20, 2025

Story of Seeds: How Participatory Video Is Revitalizing Culture and Conservation in Remote Communities

Some of my most cherished memories revolve around stories shared beneath the gum trees - timeless wisdom exchanged by those whose hands were stained with the red sands of the Central deserts. Many years ago, I came across an old, grainy video featuring an elder who recounted how her grandmother would gather the plants and prepare traditional bush medicines. This historical footage served as a cornerstone for establishing the Mukurtu archive within the community.This article is about communities seizing the opportunity to capture their narratives and preserving their stories of seeds. Through Participatory Video, First Nations people are engaging their elders and transforming seed banks into repositories of cultural memory while facilitating intergenerational knowledge transfer. The seed is the embodiment of limitless potential.How a Camera Becomes a Campfire: The Transformative Role of Participatory VideoParticipatory video (PV) is more than a method—it's a movement that brings First Nations storytelling to the forefront, especially in remote communities. When I first witnessed PV in action, it was clear that the camera had become a new kind of campfire. Around it, elders and youth gathered—not as passive subjects, but as active informants and directors of their own narratives. This shift is profound. Research shows that PV allows Indigenous communities to control their own storytelling and video production, restoring video as a truthful communication tool and a vessel for cultural heritage.In each of our seed bank projects, we teach workshops on Participatory Video to document the journey and develop a way to for each community to tell their own stories and use these for community engagement, archival use and impact reporting. I’ve seen how PV transforms documentation into shared storytelling. For example, a young woman’s first bush tomato gathering with her grandmother isn’t just a memory—it’s a living story, captured on film and woven into the community’s collective narrative. These personal accounts connect past and future, ensuring that knowledge isn’t lost but passed on, voice by voice, frame by frame. The emotional resonance is powerful: pride, hope, and resilience shine through in every genuine on-camera moment, far surpassing any scripted message.PV also fosters pride and visibility for communities often marginalized in mainstream media. By inviting everyone—elders, women, youth—to participate, the process becomes a celebration of identity. I remember a community elder’s words during a seed bank project:This seed bank is not just about seeds; it’s about our future, our stories, and our culture.That statement became a beacon for real change, echoing through every stage of the project. The video stories we created serve as both an archive and a tool for reporting. They double as powerful advocacy to attract resources and understanding from outsiders. For instance, a recent $50,000 grant was secured thanks to a PV documentary that showcased the impact of the seed bank initiative. These stories speak directly to funders, policymakers, and the broader public, offering a window into the community’s aspirations and achievements.Community screenings, like the one held in community in June 2021, turn these videos into moments of celebration and collective action. Families, leaders, and external stakeholders come together, their pride evident as they watch their own stories unfold on screen. These events are more than just viewings—they are affirmations of cultural heritage and unity, sparking conversations about the importance of conservation and the ongoing stewardship of local biodiversity.Ultimately, participatory video empowers remote Aboriginal communities to tell their own stories, transforming the simple act of video-making into a force for cultural preservation, advocacy, and intergenerational connection. Each genuine story fragment—each unscripted moment—grounds the project in lived truth, ensuring that the legacy of culture and conservation endures.Gatherings Under Gum Trees: The Art (and Imperfection) of Stakeholder EngagementWhen I reflect on the heart of our seed bank projects, it’s not the equipment or the funding that comes to mind first—it’s the gatherings under gum trees, the laughter echoing while collecting seeds, and the sense of belonging that grows with every shared story. Community engagement, in this context, is never a checklist. It’s an evolving, sometimes unpredictable process that thrives on genuine connection and collective purpose.Our initial meetings are intentionally held in culturally significant places—often beneath the shade of gum trees or in dry river beds. Here, elders, youth, women, and men come together, not as stakeholders in the corporate sense, but as family and knowledge holders. These gatherings set the tone for the entire Participatory Video (PV) process. There’s no rigid agenda. Instead, the energy is more like a yarning circle than a boardroom—open, conversational, and, at times, beautifully chaotic. And there is always plenty of tea.Workshops are designed for authentic participation with a giant roll of butcher paper and handfulls of markers. Sometimes, this means crazy drawings, dogs barking in the background, or heated debates about the best way to collect, clean and store seeds. Far from being distractions, these moments are the fabric of real community workshops. As one participant put it,Our best stories started as arguments about how to store seeds. It takes all voices.This approach to stakeholder engagement is deeply relational. Trust is built slowly—through patience, shared meals, and the willingness to listen, not through policy documents or formal agreements. Research shows that these inclusive, organic workshops are vital for the long-term sustainability of seed bank projects and seed storage practices. They foster consensus and reinforce community identity, ensuring that everyone feels invested in the project’s direction.Inclusivity is more than a goal; it’s a lived reality. We structure these workshops for youth, elders, and women, aiming to give everyone a voice. Sometimes, the process reveals unexpected leaders—a quiet elder who becomes the group’s storyteller, or a young woman who, after interviewing her grandmother on camera, finds her own voice as a cultural advocate. These intergenerational knowledge sharing moments are where the real magic happens. Youth learn by doing, elders pass on traditions, and together, we create a living archive of community wisdom. Seed conservation and storytelling go hand in hand, both are crucial for adapting to climate change and ensuring cultural survival in the face of environmental challenges.The Indigenous Land and Sea Corporation, regional media centres and NIAA have all been instrumental in supporting these efforts, providing resources that allow us to blend technical training with cultural priorities. But the true strength of our stakeholder engagement lies in its imperfection. It’s messy, unpredictable, and utterly human. And that’s exactly what makes it work.In these gatherings, consensus isn’t forced—it emerges. Community workshops become spaces where identity is not only discussed but lived, and where the seeds of both culture and conservation are sown for generations to come.Bush Tomatoes and Living Archives: Co-Creating Biodiversity PreservationIn remote Aboriginal communities, biodiversity preservation is not just about protecting plants—it’s about keeping culture alive. When we set out to create a seed bank, the first step is always a genuine, cross-generational conversation. Choosing which species to protect, like bush tomato and Mulla Mulla (Ptilotus spp.), isn’t a decision made in isolation. Elders, youth, and everyone in between gather, sharing stories and knowledge to guide our selection. This process ensures that our seed banks reflect both ecological value and deep cultural significance.Seed collection is where teaching, memory-making, and fun come together. I remember watching Asha, a young woman from of the the communities we work in, collect bush tomato seeds with her grandmother. The sun was hot, and they spread the seeds on flat stones to dry, laughing and telling stories as they worked. These moments are more than practical—they’re about cultural transmission. As Asha later shared,I can still smell the bush tomato on my hands every time I watch the video of us collecting.Documenting these activities through Participatory Video (PV) transforms each step into a living tutorial and a time capsule. Our videos capture not just the how-to of bush tomato seed collection, but the why—preserving the stories, songs, and laughter that make these practices meaningful. Research shows that PV is a powerful tool for engaging all generations, giving everyone a voice and ensuring that knowledge is passed on authentically.When it comes to sustainable seed storage, the conversation gets lively. Storage isn’t just science; it’s about trust. Grandmothers advocate for time-tested plastic buckets, while tech-savvy youth suggest airtight containers or even recycled packaging. Sometimes, debates over which basket is best can get heated, but these discussions are part of what makes our approach strong. We blend traditional and modern techniques, always guided by what works best for each unique environment.Throughout, we document every step—sun-drying seeds, winnowing & cleaning them, and carefully labeling and placing them in their chosen vessels. Our videos serve as a visual reference, ensuring that future generations can learn directly from our experiences. This living archive is more than a record; it’s a bridge between past and future, tradition and innovation. As we store seeds of bush tomato, native wattle, and Cymbopogon ambiguus, we’re also storing stories, memories, and hope.Research indicates that seed banks are vital for both biodiversity preservation and cultural heritage. By linking our seed bank activities with community storytelling and education, we ensure that our efforts are sustainable and meaningful. The interplay of tradition and innovation, moments of meaning captured on video, keeps our culture vibrant and our biodiversity protected for the long haul.From Footage to Film: The Patchwork Craft of Collaborative EditingCollaborative editing is where the heart of community storytelling truly comes alive. In our experience working with Participatory Video (PV) in remote Aboriginal communities, the editing process is never a solitary task. Instead, it’s a communal affair—often held at the local media centre, where the Wi-Fi might be slow but the tea is always flowing. Here, the act of piecing together video footage becomes an opportunity for connection, learning, and shared authorship.Training in video production is ongoing and inclusive. Elders gather with youth, each bringing their own strengths to the editing table. While younger participants might be more comfortable adjusting audio levels or splicing clips, elders contribute by recalling stories, offering context, and ensuring that the narrative remains true to community memory. This intergenerational exchange is central to our approach; it’s not just about technical skills, but about weaving together voices and perspectives that reflect the collective experience.The final film is rarely polished in the conventional sense—and that’s intentional. We celebrate the raw, unscripted moments: Tanique’s children scrambling after seeds, an elder’s off-key singing drifting over baskets of bush tomato seeds, laughter echoing in the background. These moments are the soul of community storytelling, capturing the authenticity and vibrancy of daily life. As Tanique, a community participant, once shared:Seeing my kids on the big screen collecting seeds, that’s family history—captured.Through collaborative editing, participants gain more than just video production training—they develop a sense of ownership and pride. The process ensures that the video reflects a collective memory, not a single vision. Research shows that this approach not only strengthens community bonds but also serves as a powerful tool for advocacy through video. When the finished film is shared, it’s not just a record; it’s a living testament to the community’s resilience and aspirations.Community screenings are a highlight of the PV journey. These events are more celebration than premiere. Families, elders, youth, and even outsiders gather, drawn by the promise of food, laughter, and pride. The screenings become milestones—moments that reinforce collective identity and spark dialogue about the importance of biodiversity preservation and cultural heritage. I get tears in my eyes when I talk about these moments of togetherness and hope - for me, these memories are treasures that last a lifetime.Screenings also have a strategic impact. By showcasing the community’s work, they open doors to advocacy and support. Studies indicate that advocacy through video can help secure funding and raise awareness for vital projects like seed banks. When stakeholders witness the genuine stories and community effort on screen, they are more likely to offer resources and partnership, ensuring the sustainability of both cultural and conservation initiatives.In essence, collaborative editing transforms video production into an act of shared authorship. Each screening is a celebration of community storytelling, impact, advocacy, and the enduring power of collective memory.Planting for Tomorrow: Partnerships, Persistence, and Passing it OnLooking ahead, the future of sustainable seed banks in remote Aboriginal communities rests on more than just careful collection and preservation. It thrives on the strength of our partnerships, the persistence of our efforts, and our commitment to passing knowledge from one generation to the next. Participatory Video (PV) has shown itself to be a powerful catalyst in this journey, not only documenting our progress but also amplifying our collective voice in ways that attract support and inspire action.From the outset, building strong ties with universities, NGOs, and government programs like the Land and Sea Rangers has been essential. These partnerships bring expertise, visibility, and, crucially, financial support. I’ve seen firsthand how sharing our PV stories with these partners opens doors. In fact, a recent $50,000 grant was secured after we showcased our community’s achievements through video. This wasn’t just luck; it was the result of years of community engagement and advocacy through video, demonstrating real impact and potential for growth.Annual review meetings have become a cornerstone of our approach. By gathering the community to watch and discuss the latest PV footage, we keep our seed bank initiative alive and adaptive. These reviews are more than just a look back—they are a chance to reflect, celebrate, and plan for the future. Feedback from elders, youth, and partners shapes our next steps, ensuring the project remains relevant and resilient. Research shows that this kind of ongoing, inclusive engagement is vital for long-term sustainability.There are a variety of governmental and NGO's which offer grants that are key for financial sustainability. But beyond funding, these collaborations help us access research, training, and broader networks. Each new partnership is like planting a seed—sometimes the results are immediate, other times they take root slowly, but over time, the garden grows. As one project coordinator put it,Partnerships grow like seeds—you start with one, and suddenly there’s a whole garden.Ultimately, our goal is to turn every seed bank project into a beacon for intergenerational knowledge sharing, local leadership, and biodiversity advocacy. PV doesn’t just record these stories; it helps us share them with the right people and organizations that can assist, inviting others to join us in protecting both our heritage and our environment. The process is ongoing—there’s always more to learn, more to share, and more to preserve. By staying persistent, nurturing partnerships, and passing on what we know, we ensure that our efforts today will continue to bear fruit for generations to come. Saving and sharing seeds is not just an agricultural practice, but an ethical and ecological duty to ensure future food security and biodiversity. TL;DR: Participatory Video in remote Aboriginal communities isn’t just about filmmaking: it’s about community, heritage, and hope. By blending modern video tools with old traditions, communities preserve, celebrate, and pass on their stories—and their seeds."Preserving ancient culture and saving seed is the highest moral duty on Earth"Dr.Vandana ShivaWe will share more about the Mukurtu CMS Archive system in a future post.

13 Minutes Read

Jun 20, 2025

Wattle Seeds

Today we venture out on an important journey - one that will create a link between the past and the future, expressed as a restoration project designed to create sustainable economic value while preserving biodiversity on Traditional Indigenous homelands.We are traveling to seed collection sites, located approximately 80 Km outside of this community, on a mission to preserve cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, and traditional cultural expressions. We have done nearly 250 of these trips over the years.Time is of the essence as we harvest these seeds; each collected specimen holds immense potential to restore degraded ecosystems, and ultimately, sustain biodiversity. With great care, we take only what we need, leaving behind enough for food and natural propagation. Every step we take is essential in protecting and preserving this precious genetic material.Our work today honours the reverence Indigenous Peoples have for this planet. As stewards of some of the worlds most biologically diverse areas, the experience and knowledge of First Nations people continues to be invaluable resources in developing solutions to the ever-present challenge of climate change. Our commitment lies in supporting and upholding Indigenous rights to maintain control over their cultural heritage and intellectual property.Today marks an important beginning, but it is simply one step in a much larger effort. Together, let us seize this unique opportunity to celebrate and protect these ancestral legacies, for the benefit of generations to come.Why Wattles?Wattles have always been a significant part of the Australian landscape. These iconic trees bring us beauty, joy, and environmental services like carbon sequestration and habitat provision for native wildlife. Yet, behind their beauty lies another story - one of potential, promise, and progress. It's a story of how, through years of research and development, the Acacia soligna has become more than just stunning specimen of nature.Thanks to the efforts of dedicated conservationists, this unique species has become a valuable resource - providing biomass for fuel production, seed for livestock food production, and timber and particle board for construction. Moreover, it has even become an important tool in restoring degraded lands. But its prospects don't end there.In recent years, clonal work with stem cuttings and domestication programs have given rise to new innovations in wattle seed production. Field trials and research are allowing us to match different wattle species to specific climates and soil types, giving rise to stable populations that can fulfil desired end products. Already, these advances have led to vast improvements in our ability to grow and cultivate wattles, unlocking a rich source of potential benefit for both nature and human life.The journey of wattle seed production and conservation is an inspiring one. So let us take a moment to appreciate the beauty and significance of wattles in our land, and join hands in continuing to support this important work. For it is only by doing so that we can unlock the true potential of Australia's national floral emblem and create a more vibrant future for generations to come.

3 Minutes Read

Jun 17, 2025

The Poverty of Affluence

There are no words that can accurately describe the spaciousness of the NPY lands in the Central Deserts. It is incredibly diverse and complex, a living, breathing expanse of Terra firma, where one can feel a palpable sense of the deeper invisible realms of existence. It is a place where the sunsets find their way into your dreams, medicine plants speak, and where the red sands leave their impression upon your socks and your soul. It is easy to understand the love of country for the people who call this home - it is a part of them, and they are a part of it. To witness such a deep sense of belonging to place fills me with awe and wonder.It can be demanding to live in such a remote region, yet people have thrived out on these lands for thousands of years due to their direct and very personal relationship with country. The interactions with the elders teach you to listen deeply - to notice and care for the earth that provides for all our needs. You quickly discover how little meaning your knowings have amidst this vast backdrop. There is great wisdom in simplicity.When I first came here years ago, I was struck with a sense of how little the people here had in terms of material wealth. Today, walking down the busy streets of Brisbane amidst the affluence of the modern world, I can only think of the poverty of being disconnected from the earth and not seeing the stars at night, and how abundantly rich my desert friends are, living in the moments outside of time.If you listen deeply, you can hear the whispers of eternity...

2 Minutes Read

Jun 17, 2025

Community Engagement

Every place on earth has its own unique story to tell. Take a walk in the vast expanse of the Central deserts, step into the Daintree rainforest or gaze across the timelessness of the Kimberly...you'll sense a power emanating from the land. It's not only the trees, plants and animals that occupy this space, but also the history - the stories that have been passed down through generations of humans and their complex relations with wild spaces. But how do we uncover its true identity beyond its physical features? How do we restore what we do not recognize? To do things differently we must see things differently. - John Thackara We must dive into the 65,000-year history of human and nature co-existence; an intertwined story of the forces that have shaped the land, crafting a core identity that makes each place unlike any other on Earth. This interplay is what creates a sense of place: a harmony of human culture, geology, climate, and biodiversity that marks it apart from anywhere else in the world. What's more, each community has a unique relationship with the environment - the ways people have interacted and coexisted with land and wildlife for generations. Regional cultures carry stories of true-life self-determination and community-led change, and traditional songs are storehouses of localized ecological knowledge.This notion of place, coupled with the issues of cultural significance to indigenous communities, are at the heart of Bush Botanics' efforts to bring together traditional knowledge and spiritual leadership to inform our nature restoration and small-scale enterprise projects. Our approach recognizes the importance of engaging directly with indigenous communities for proper representation, reconnecting humanity's shared history with nature and developing region-specific protocols rather than relying on generic best practices.Indigenous Peoples have always been on the front line of the environmental crisis. For generations First Nations peoples have used systems of traditional knowledge to manage and safeguard diverse natural environments, including our World Heritage sites and land and ocean resources. Currently, the Indigenous Rangers Program supports more than 2,100 jobs in land and sea management through 129 First Nations ranger groups working On-Country. This work has been augmented by the Indigenous Protected Areas Program, which covers eighty-two dedicated sites across Australia and is growing. Indigenous Peoples possess solutions not only to their own problems but also to the global challenges facing humanity. Their cultures serve as models for the future in a world searching for new value systems, and First Nations peoples are now acknowledged as essential for nature conservation. UN biodiversity scientists from the IPBES found that biodiversity declines at a slower rate on Indigenous-managed lands compared to other lands, however, many conservation efforts have neglected the rights of Indigenous peoples, preventing them from living on their own lands in the name of conservation. These same Aboriginal groups have long been custodians to some of the most complex ecosystems in the world. It is said little can tear at the heart more than being forced to abandon the place of your ancestors. The respect that Indigenous Peoples have for the earth is a concept foreign to Western civilization.¬They are the stewards of some of the worlds most biologically diverse areas, and their traditional knowledge about the biodiversity of these areas is invaluable. As the effects of climate change become evident, it is clear that Indigenous Peoples must play a central role in developing adaptation and mitigation efforts to this global challenge. State of the Worlds Indigenous PeoplesIf we want to build a sustainable future, it is crucial to recognize the importance of local knowledge and understanding regional custodians on their terms. There is no future without putting the perspectives and experiences of our First Nations people at the forefront of our environmental activities. Remembering our dependence on unique places and the ways they have sustained humanity for generations may be the key to unlocking the planet's potential. By learning to appreciate this sense of place, we can nurture mutual prosperity between humans and nature for long-term good.Community engagement must go beyond the occasional yet essential 'welcome to country' and the casual conversations that are often represented as 'partnerships'. The Australian Human Rights Act 2019 and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples aim to acknowledge the ethical and practical considerations necessary for engaging with First Nations communities and their cultural and ecological materials. For true community engagement, there must be a commitment to ensure First Nations' environmental, cultural and community values are ethically and respectfully engaged. Who holds the song for the plant varieties used in restoration projects? Who is culturally authorized to consent to restoration activities? Is the long-term welfare of the local Indigenous community and their ability to remain on-country a part of the plan?Today, industries often use environmental and sustainability claims, as well as claims of Indigenous partnership, which can mislead consumers. The following guidelines identify areas where both businesses and consumers need more guidance. In the age of big restoration projects, it is crucial to listen to the human voices, experiences, and stories behind the numbers. These narratives can bring to life the true impacts of restoration programs, share sidelined perspectives, and foster new innovations, connections, and reconciliation.Effective community engagement recognizes and respects the crucial place of First Nations culture and stories at the centre of Australia's environmental heritage, and is founded on the following ten principles for respecting Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property; respect, self-determination, consent and consultation, interpretation, cultural integrity, secrecy and privacy, attribution, benefit sharing, maintaining First Nations culture, and recognition and protection (Janke 2021). If you are working in ecological restoration, consider these active points of engagement as a way to explore some of the deeper questions and values around sustainability, including the nature of evolution and the role of human beings in the natural environment;Involvement with First Nations peoples as key leaders and decision-makers in planning, policy and engagement. Organizations are required to have proper consultation, consent and permissions for working with First Nations ecological materials as part of their restoration plan. Have you checked what and whose cultural permissions must be sought prior to going forward with your project, and are you ready to accept their advice and decisions? Are you mapping the important historical human and biological systems in the region?Organizations must invest in dedicated programs and initiatives that support career development and cultural practice of First Nations workers. What percentage of your staff and on-country restoration workers are of First Nations identity?Acknowledge the ethical, intellectual and cultural heritage property rights of First Nations people in ecological resources. How are you and your organization acknowledging and celebrating First Nation cultural contributions in your projects? Are First Nations practitioners leading the planning and delivery of the restoration work? Do you have the proper and appropriate permissions to gather seeds and other ecological materials?Do you have an Indigenous Engagement Strategy? What are the mutual benefits of your restoration project? Are you sharing the learnings and financial benefits?Are there First Nations members on your board and in key leadership positions within your organization? How are you as an employer supporting the professional development of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander employees?These guidelines should be considered standard for the protection of the survival of First Nations as distinct peoples and are intended to address the challenges Indigenous people face around the world. Transparency and verification will be clearly expressed on the websites of those organizations that are doing it right. The most vulnerable communities around the world are those that still hold an intricate knowledge of local cultural and biological diversity. Such forms of local knowledge (sometimes referred to as Traditional Ecological Knowledge, TEK) is vital to the survival of the planet, and disappearing fast. In a deeper sense, engaging appropriately with cultural practice and the custodians who hold it, is one of the main hallmarks of successful restoration impact. Join us on this journey towards healing nature and restoration for people and the planet, walking together as we use our imagination and creativity to dream a more flourishing and compassionate world.

7 Minutes Read

Jun 17, 2025

Building a Restoration Economy

When I first came to the Central Deserts, Australia was in the midst of one of the driest seasons in recent memory. The weather people called it an 'El Nino', which has no direct translation in Pitjantjatjara, a dialect of the Western Desert language traditionally spoken by the people of Central Australia. Working in some of the most remote regions of the world with traditional bush foods and botanicals, I noticed there were few seeds for collection on the trees and grasses. In my mind I was immediately taken back to my seventh-grade science teacher Mr.Bliss, and the posters on the classroom wall featuring the Life Cycle of a Flowering Plant - most all plants need water for this process to occur. When I inquired to the elders about the lack of seeds, they pointed to the skies and replied simply, "something is broken".something is broken..."- Indigenous EldersI didn't have a term for it at the time, but this was the start of my journey into nature restoration & regeneration. It seems an obvious life path when one considers how we are operating in an extraction-based capitalist system which is destroying the foundations of our natural world.When working in Indigenous communities I started to understand the whole concept of building a restoration economy - taking the situation that’s been damaged and working together to bring it back to more of its natural state. Using our greenhouses to plant trees for restoration, and bush foods and traditional medicine plants for essential oils, the opportunity for small-scale enterprises started to form the beginnings of a localized sustainable economic model as a key element of this restorative process - one that puts people, food, culturally-aligned employment and the planet at the heart of a healthy economic engine. Native plants are also first foods, which goes back to the historical land management practice. These are the plants that kept us alive on the landscape. They can be used for restoration, used for food, used for culture. Jeremiah Pinto, U.S. Forest Service Research Plant Physiologist and Tribal Nursery Specialist.Typically when you talk about restoration, people think of trees. What is equally important is the biodiversity found in the understory. There are degraded lands all over the world that are located in a wide variety of bio-regions - this restoration work needs more than trees. What species are native and culturally important to these places?In today's rapidly changing world, the preservation and restoration of biodiversity have become crucial for the survival of our planet. One effective approach that has gained recognition is the establishment of Indigenous community seed banks. These seed banks play a vital role in safeguarding traditional knowledge, preserving native plant species, and promoting ecological restoration.Indigenous communities have long been the custodians of their lands and have developed a deep understanding of their local ecosystems. They possess valuable knowledge about the diverse plant species that are native to their regions and have traditionally used these plants for various purposes, including food, medicine, and cultural practices. However, with the increasing threats of climate change, deforestation, mining, and industrial agriculture, many of these native plant species are at risk of extinction.To combat this loss of biodiversity, Bush Botanics has been working with Indigenous communities to establish localized community seed banks. These seed banks serve as repositories for storing and conserving seeds of native plant species. By collecting and preserving these seeds, Indigenous communities ensure the availability of locally adapted plant varieties that are resilient to changing environmental conditions.The indigenous people have a deep connection to the existing plants, and for centuries have been managing them through their natural nurseries, controlled burning, seed-saving, and transplanting specific varieties. How can we integrate this ancient traditional ecological knowledge into our restoration efforts while maintaining cultural ties?The seed banks not only act as conservation centers but also serve as educational hubs. Indigenous communities actively engage in seed-saving practices, passing down traditional knowledge from one generation to another. At our seed banks we conduct workshops, community engagement and training sessions to educate community members about the importance of seed diversity and sustainable land management practices. This knowledge exchange fosters a sense of pride in cultural heritage and strengthens community resilience.Wild-collected native seeds, which are seeds obtained from their natural habitats, play a crucial role in preserving the evolutionary history and cultural legacy of specific environmental genes. These seeds are often subjected to harsh environmental conditions, ensuring that the genetic diversity and adaptability of these seeds are maintained, allowing them to thrive in various environmental conditions. This approach not only safeguards the long-term survival of these plant species but also contributes to the conservation of their unique genetic traits.Indigenous community seed banks prioritize the use of organic and traditional growing methods and promote agro-ecological practices that are in harmony with nature, such as intercropping and natural pest control. By doing so, they contribute to the overall health of ecosystems while eliminating the use of chemical inputs that can cause long-term harm to biodiversity, people and to the planet.The benefits of Indigenous community seed banks extend beyond conservation efforts. They also play a crucial role in supporting food security and sovereignty. By preserving a wide range of plant species, these seed banks ensure access to diverse and nutritious food sources and small-scale income in the native food and botanicals marketplace. Additionally, they empower Indigenous communities by giving them control over their biodiversity resources and reducing their dependence on external sources for seeds and food.In recent years, the importance of our approach to Indigenous community seed banks has been recognized with the First Nations Seed Bank having been awarded the Environmental Action award in the Northern Territory. Government and partner organizations are helping to support our efforts in seed conservation and restoration work in Indigenous communities. Funding and technical assistance are being provided to strengthen the infrastructure of these seed banks and expand their reach.Indigenous community seed banks are an essential tool for the restoration of biodiversity. They not only conserve native plant species but also preserve traditional knowledge and promote sustainable farming practices. By empowering Indigenous communities to take charge of their genetic resources, these seed banks contribute to food security, cultural resilience, and the overall well-being of our planet. It is crucial that we continue to support and learn from these initiatives to ensure a sustainable future for all.

6 Minutes Read

May 14, 2025

Nurturing Tradition: The Role of Community Seed Banks in Aboriginal Australia

As I reflect on my journey working across various Aboriginal communities, I have seen firsthand the power of seed banks and the community engagement which drives them—not just as a method of safeguarding biodiversity, but as living libraries of culture and resilience. It is here, nestled in the stories of elders and the ancient practices on-country, that the real impact of these community seed banks unfold.The Essence of Community Seed BanksWhat Are Community Seed Banks?Community seed banks are more than just storage facilities for seeds. They are vital hubs for preserving local plant varieties and connecting the seeds to the traditional cultural relationships. These seed banks aim to maintain genetic diversity among plants that are crucial to a community’s identity and food security. Think of them as living libraries of seeds, where each seed tells a story. They hold the potential to sustain communities, especially in times of climate change.Historical Significance in Indigenous CommunitiesIn Indigenous communities, seed banks carry a rich history. They are not just about agriculture; they are about culture. Each seed represents generations of knowledge and tradition. For instance, the bush tomato is more than a food source; it embodies the survival and practices of a community. As one Indigenous Knowledge Keepers said,“Seeds carry stories just as much as they carry life.” This connection to the past is crucial for cultural identity - the seed is the vital link between preserving the traditional stories that connect culture to each seed variety. This is how traditional knowledge is passed on...The Importance of Community InvolvementCommunity involvement is the backbone of successful seed banks. Without the active participation of local people, these initiatives can falter. Engaging with community members during the planning stages is essential, ensuring the seed bank reflects the needs and values of the community. I’ve seen how consultations with elders and youth can shape the vision of a seed bank and awaken a cultural resurgence within communities.Connection to Food SecurityFood security is a pressing concern worldwide, and the community seed bank network can play a pivotal role in ensuring remote communities can grow crops that are well-adapted to their environment. This is especially important as climate change threatens farming systems and remote food distribution. When communities have access to diverse seeds, they can cultivate resilience.Preserving Genetic DiversityOne of the primary purposes of community seed banks is to preserve genetic diversity among local plants. This diversity is crucial for adapting to changing environmental conditions. It allows communities to respond to challenges like drought or pests. By saving seeds, we are not just saving plants; we are safeguarding our future.Building Community Resilience Community seed banks are essential for preserving biodiversity, cultural heritage, and food security. They are a testament to the strength and resilience of Indigenous communities. Each seed holds a story, and together, they weave a narrative of survival and hope.

3 Minutes Read

May 14, 2025

That time I sued Monsanto...

Back in 2010 I was sitting at a table with a group of organic seed farmers after just having listened to Percy Schmeiser give a talk about his experiences with Monsanto. Without resources or financial help, 70-year-old Percy Schmeiser engaged in a modern day David vs. Goliath endeavor and created a ray of hope among farmers all around the world. Nearly a decade earlier I had spent a year in India with my mentor and friend Dr.Vandana Shiva, visiting the devastated communities and families who were impacted by the wave of farmer suicides caused by Monsanto GMO technology having failed small farmers. And here they were again, the beast was right in my backyard with their acquisition of Seminis seeds." Corporations are nothing but a glorified parasite leaching blood out of our society. For a businessman, it is the profit that matters and not cultural values. However, are we going to take a stand against those Goliath who ruins our roots? Or will we just stand and watch? "Percy SchmeiserWorking as part of a group of organic seed famers, my company, Edible Gardens, operated an heirloom seed grow operation in the fertile Santa Barbara hinterland. All of us in OSGATA recognized we were at risk of losing everything if Monsanto ever targeted one of our operations.At that table we decided to spearhead a lawsuit against biotech giant Monsanto to challenge the company’s patents on genetically modified seed...The lawsuit was filed on behalf of the group of farmers, including my company Edible Gardens, by the Public Patent Foundation . The suit was filed in federal district court in Manhattan.“St. Louis, Mo.-based Monsanto has sued farmers for patent infringement in cases where the company’s genetically modified seed has landed on the farmers’ property,” Dan Ravicher, lead attorney in the case and the Public Patent Foundations’s executive director, said in a statement. “It seems quite perverse that a farmer contaminated by GM seed could be accused of patent infringement, but Monsanto has made such accusations before and is notorious for having sued hundreds of farmers for patent infringement.”The lawsuit asks the court to declare that if farmers are ever affected by Monsanto’s modified seed, they cannot be accused of or sued for patent infringement.Organic farmers have been angered by the use of genetically modified seed because it damages their organic seed when it spreads. According to the statement, organic canola seed has become virtually extinct since Monsanto introduced genetically modified canola seed, and “organic corn, soybeans, cotton, sugar beets and alfalfa now face the same fate.”“Santa Barbara is a community with a rich agricultural heritage and an abundance of organic farmers,” said William Martin, president of Edible Gardens and a plaintiff in the lawsuit. “Once a natural seed variety is contaminated, there is no turning back — the genetics are altered forever. Under the current patent laws, these seeds and the crops are considered the property of Monsanto, which has a vested interest in eliminating natural, open-pollinated varieties.“We are on the verge of losing, in one generation, much of the agricultural diversity humankind created in the last 10,000 years. Our future will depend on how well we steward our precious resource of natural seeds and pass them on to future generations.”The lawsuit comes on the heels of a recent USDA decision to deregulate genetically modified alfalfa, despite court rulings against the planting of these crops.It was standing room only as family farmers from around North America filled Federal Court Judge Naomi Buchwald's courtroom in Manhattan on Tuesday, January 31. The topic was the landmark organic community lawsuit OSGATA et al v. Monsanto and the oral argument Monsanto's pre-trial motion to dismiss which it filed last July. Plaintiffs from at least 21 States and Provinces were in the courtroom including Oregon, California, New Mexico, Colorado, Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota, Saskatchewan, Missouri, Iowa, Ohio, Florida, North Carolina, Virginia, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, New York, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Vermont and Maine."We were very pleased that the court granted our request to have oral argument regarding Monsanto's motion to dismiss our case today," said Daniel Ravicher of the Public Patent Foundation, lead lawyer for the Plaintiffs. "The judge graciously permitted both parties to raise all the points they wished in a session that lasted over an hour. While Monsanto's attorney attempted to portray the risk organic farmers face from being contaminated and then accused of patent infringement as hypothetical and abstract, we rebutted those arguments with the concrete proof of the harm being suffered by our clients in their attempts to avoid such accusations. The judge indicated she will issue her ruling within two months. We expect she will deny the motion and the case will then proceed forward. If she should happen to grant the motion, we will most likely appeal to the Court of Appeals who will review her decision without deference." After the conclusion of the courtroom oral argument, the plaintiff farmers and their legal team from the Public Patent Foundation provided details and comments on the courtroom proceedings, to supporters at the Citizens' Assembly.The large group of 83 Plaintiffs in OSGATA v. Monsanto is comprised of individual family farmers, independent seed companies and agricultural organizations. The Plaintiffs are not seeking any monetary compensation. Instead, the farmers are pre-emptively suing Monsanto and seeking court protection under the Declaratory Judgment Act, from Monsanto-initiated patent infringement lawsuits. Early on in the legal process, Monsanto was asked by lawyers for the Plaintiffs to provide a binding legal covenant not to sue. Monsanto refused this request and in doing so made clear that it would not give up its option to sue contaminated innocent family farmers who want nothing to do with Monsanto's GMO technology.In a remarkable demonstration of solid support by American citizens for family farmers, co-plaintiff Food Democracy Now! has collected over 100,000 signatures on it's petition supporting the rights of family farmers against Monsanto. For the past 12,000 years farmers have saved the best seeds each year to increase yields and improve traits for the food we eat. In 1996, when Monsanto sold its first patented genetically modified (GMO) seed to farmers, this radically changed the idea of how farmers planted and saved seed. Less than two decades later, Monsanto's aggressive patent infringement lawsuits have created a climate of fear in rural America among farmers. It's time for that to end. Farmers should not have to live in fear because they are growing our food.For those who want to know the legal details...Organic Seed Growers and Trade Association's suit against Monsanto, 2012 and 2013By: Ernest Nkansah-Dwamena, used under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0) Published: 2014-12-30In March 2011 the Organic Seed Growers and Trade Association and around sixty agricultural organizations (OSGATA et al. ) filed a suit against Monsanto Company and Monsanto Technology L.L.C., collectively called Monsanto. The hearings for Organic Seed Growers and Trade Association (OSGATA) et al. v. Monsanto (2012) took place at the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York in Manhattan, New York. The district court's Judge Naomi Reice Buchwald dismissed OSGATA's suit. A year later, OSGATA appealed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in Washington, D.C., and the court agreed with the District Court's 2013 decision. OSGATA appealed to the US Supreme Court in late 2013, and the Supreme Court refused to hear the case in 2014. In the OSGATA et al. v. Monsanto case, OSGATA claimed that genetically modified seeds are a threat to both human health and conventional and organic farming. OSGATA petitioned that because of this threat, twenty-three of Monsanto's patents on genetic modification processes and technologies were invalid.Monsanto manufactures, licenses, and sells agricultural seed varieties that are genetically modified, also called transgenic seeds. To produce genetically modified crop varieties, scientists alter the variety's genetic material (DNA) by incorporating into the organisms of that variety genes and regulatory sequences that those organisms don't normally have. This process is called genetic engineering or agricultural biotechnology. Scientists modified several different crop varieties to express traits in crops such as herbicide tolerance and pest resistance. These crop varieties became commercially successful because the engineered traits protect crops yields under adverse circumstances. Some of Monsanto's most popular genetically modified varieties are called Roundup Ready. Those varieties tolerate exposure to the herbicide glyphosate, commonly called Roundup, which enables farmers to control weeds without damaging their crops.In the early decades of the twenty-first century, Monsanto was the world's largest seed producer and controlled about 85 percent to 90 percent of the seed market for soybeans, corn, cotton, sugar beets, and canola grown in the US. Monsanto relied on patents to protect its investments in seeds, traits, and production biotechnologies, and Monsanto licensed its patents to other seed companies. Monsanto permitted farmers to use its patented seeds under a limited-use license, which allowed farmers to plant, harvest, and consume or sell patented crops in a single growing season. A limited-use license did not allow farmers to save any of the harvested crops for replanting or to supply to other farmers.OSGATA is a coalition of farmers, seed growers' associations, seed distributors, agricultural organizations, and public advocacy groups headquartered in Washington, Maine. According to OSGATA, they represented about 300,000 individuals and 4,500 farms or growers who had no interest in genetically modified seeds and do not use or wish to possess or sell any genetically modified seeds, including those covered by Monsanto's patents. OSGATA said that even though they did not use Monsanto's seeds, their crops could become contaminated by genetically modified varieties. Inadvertent contamination may occur through seed drift or scatter, crosspollination, and during harvest or postharvest activities such as transportation, and storage. As a result, Monsanto could sue for patent infringement should Monsanto's genetically modified seeds contaminate OSGATA members' farms. OSGATA was also concerned that transgenic contamination would cause farmers to lose their organic certification from the US Department of Agriculture, located in Washington, D.C.OSGATA preemptively sued Monsanto based on these issues. On 29 March 2011, OSGATA filed a complaint against Monsanto at the Southern District Court of New York. They sought a declaratory judgment that twenty-three of Monsanto patents were invalid, unenforceable, and not infringed under the Patent Act. OSGATA argued that Monsanto's genetically modified seeds were not safe for societal use, and were invalid under the Patent Act, which says that only technology with beneficial societal use may be patented. OSGATA argued that Monsanto's genetically modified seeds worsen people's health.In their argument, OSGATA asserted that genetically modified crops are indistinguishable to the human eye from conventional varieties. OSGATA claimed that genetic testing, the only proactive way to detect genetically modified contamination, is expensive, and that contaminated crops must be completely destroyed. Further, OSGATA claimed that the constant threat of genetically modified seed contamination could destroy their market. In addition, they said that they had the right to do their businesses without taking expensive precautions that lessen their risk of contamination.In April 2011, after filing the original complaint, OSGATA requested in a letter that Monsanto sign a written waiver that protected OSGATA from claims of patent infringement. Monsanto denied that request and responded that it was not their policy to exercise patent rights against farmers whose fields inadvertently contained trace amounts of patented seeds or traits. According to Monsanto, a written promise not to sue OSGATA was unnecessary because the company had no incentive to sue OSGATA. In July 2011, Monsanto filed a motion to dismiss the case for lack of subject matter jurisdiction, arguing that OSGATA had failed to allege an actual case or controversy. Subject-matter jurisdiction is the authority of a US court to hear cases of a particular type or cases relating to a specific subject matter or controversy initiated in its court.The United States District Court for the Southern District of New York called an oral hearing in January 2012 to hear both parties' cases. Then in February 2012 judge Buchwald dismissed OSGATA's petition against Monsanto. The district court judge compared OSGATA v. Monsanto's case to MedImmune, Inc. v. Genentech, Inc., a US Supreme Court case from 2007. Buchwald considered whether, under MedImmune, Inc. v. Genentech, Inc. (2007), there was a substantial controversy between the two parties to warrant a declaratory judgment. Because Monsanto had never demanded royalty payments from OSGATA or identified any OSGATA conduct as potentially infringing on patents, the judge ruled that there was no substantial controversy. OSGATA based their argument on three types of alleged actions by Monsanto, none of which the judge considered to be a substantial controversy. First, Monsanto's alleged pattern of litigating against non-OSGATA farmers over patent rights. Second, an implicit threat in Monsanto's statement to not enforce their patent rights against farmers whose crops inadvertently acquired trace amounts of patented seeds or traits. Third, Monsanto's refusal of OSGATA's request to provide a written promise not to sue them.The district court ruled that OSGATA did not establish a substantial controversy or case. Buchwald ruled that if Monsanto did present OSGATA with a lawsuit, OSGATA could establish a case or controversy. The judge found that OSGATA overstated their allegations about Monsanto's patent enforcement and previous lawsuits, and that the number of lawsuits Monsanto had filed represented only a small portion of farms in the US. The court also ruled that OSGATA's attempt to demand from Monsanto a written promise not to sue was an attempt to create a controversy.In March 2012, OSGATA filed an appeal with the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in Washington, D.C., to reverse the lower court's decision. In June 2013 Judge William Curtis Bryson, Judge Timothy Belcher Dyk, and Judge Kimberly Ann Moore presided over the hearing with Attorney Daniel Ravicher and Attorney Seth Waxman representing OSGATA and Monsanto, respectively. The three judges affirmed the lower district court's dismissal. They concluded that there was no case or controversy because Monsanto had made binding assurances that it would not take legal action against farmers whose crops might inadvertently contain traces of genetically modified traits, which the court defined as less than one percent. Monsanto had agreed "not to take legal action against growers whose crops might inadvertently contain traces of Monsanto biotech genes (because, for example, some transgenic seed or pollen blew onto the grower's land)."The judges asserted that Monsanto was legally bound by its commitment to not sue OSGATA for patent infringement through inadvertent contamination of Monsanto's seeds or traits, and that the commitment would be upheld if Monsanto changed its position. The court noted that if OSGATA or other farmers behaved outside of the limits inadvertent contamination, Monsanto's promise could not be upheld. Because OSGATA said that they would not intentionally use Monsanto's seeds, the judges ruled that OSGATA presented insufficient controversy that merited no declaratory judgment. Finally, the judges found that OSGATA's concerns about the environmental and health effects of genetically modified seeds were outside the scope of this case, which focused on patent rights.OSGATA's final appeal against Monsanto occurred at the level of the US Supreme Court. In September 2013 OSGATA petitioned the US Supreme Court, located in Washington D.C., to hear its case against Monsanto. In January 2014 the Supreme Court did not select OSGATA's case for review.SourcesBartz, Diane, and Carey Gillam. "Monsanto Critics Denied U.S. Supreme Court Hearing on Seed Patents." Scientific American , January 13, 2014. http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/monsanto-critics-denied-us-supreme/ (Accessed August 6, 2014).MedImmune Inc. v. Genentech Inc. 549 U.S. 118, 127 (2007). http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?q=MedImmune,+Inc.+v.+Genentech&hl=en&as_sdt=806&case=14388218096121279792&scilh=0 (Accessed August 19, 2014).Organic Seed Growers and Trade Association. "OSGATA et al. v. Monsanto." List of documents. http://www.osgata.org/osgata-et-al-v-monsanto/ (Accessed August 6, 2014).Organic Seed Growers and Trade Association v. Monsanto Company and Monsanto Technology LLC. 851 F. Supp. 2d 544 (S.D.N.Y. 2012). http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=13942448824363195966&q=Monsanto+Company+v.+Organic+Seed+Growers+and+Trade+Association+(OSGATA),+Et+al.,+(2011)&hl=en&as_sdt=806&scilh=0 (Accessed August 6, 2014).Organic Seed Growers and Trade Association v. Monsanto Company and Monsanto Technology LLC. 718 F.3d 1350 (4th Cir. 2013), cert. denied, 134 U.S. 901 (U.S. Jan. 13, 2014). http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?q=Monsanto+Company+v.+Organic+Seed+Growers+and+Trade+Association+(OSGATA),+Et+al.,+(2011)&hl=en&as_sdt=806&case=8314236949096655850&scilh=0 (Accessed August 6, 2014).Ravicher, Daniel B. "An overview of OSGATA, et al. v. Monsanto." In Strengthening Community Seed Systems. Proceedings of the 6th Organic Seed Growers Conference. Port Townsend, Washington, USA, 19–21 January, 2012 . Port Townsend, Washington: Organic Seed Alliance, 2012: 140–3. http://www.seedalliance.org/uploads/2012%20OSGC%20Proceedings%20FINAL.pdf (Accessed August 6, 2014).

14 Minutes Read

May 14, 2025

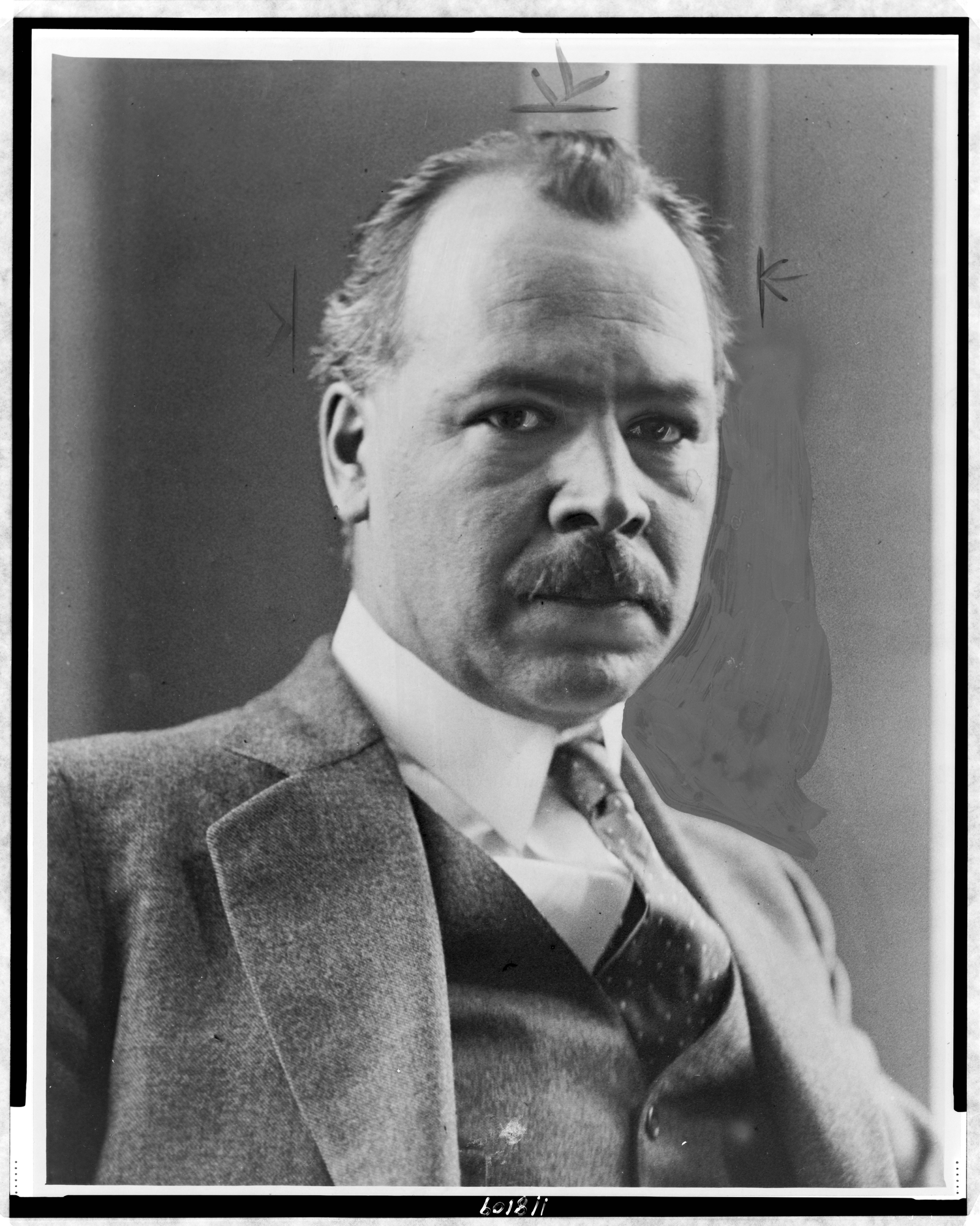

The Legacy of Nikolai Vavilov: Seeds of Change in Science and Society

When I first encountered the story of Nikolai Vavilov, I felt like I was reading a gripping novel filled with adventure, tragedy, and heroism. The tale of this Soviet botanist is not merely academic; it feels deeply personal, shedding light on a figure who dedicated his life to saving the world's plants, only to be tragically persecuted for his beliefs. Vavilov’s work resonates even today, inspiring our efforts to create community seed banks that honour both science and cultural heritage.Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov was not just a scientist; he was a visionary. His relentless pursuit of genetic diversity in plants has paved the way for sustainable agriculture. But who was Vavilov, and why is his story so significant today? Let’s dive into the life of this remarkable botanist and the impact of his work.Early Life and CareerBorn in Moscow in 1887, Vavilov developed a fascination with plants early on. After studying at the Moscow Institute of Agriculture, he became captivated by the principles of genetics, particularly those laid out by Gregor Mendel. Imagine a young scientist, much like Indiana Jones, embarking on adventures to collect seeds from around the globe. That was Vavilov. His travels were not just for personal gain; they were driven by a mission to improve Russian agriculture, especially after the devastating famine of 1921-1922.By the end of 1924, Vavilov had amassed over 60,000 seed varieties, establishing one of the first and most comprehensive seed banks. This was no small feat! His dedication to understanding plant immunity and disease resistance laid the groundwork for future agricultural advancements.Contributions and PersecutionVavilov’s groundbreaking research helped illuminate the origins of domesticated crops. He founded the All-Union Institute of Plant Industry, now known as the N.I. Vavilov Research Institute of Plant Industry (VIR). His work was crucial in collecting and improving plant varieties essential for Russian agriculture. However, his scientific integrity put him at odds with Trofim Lysenko, whose flawed ideas gained favor under Stalin’s regime.In 1940, Vavilov was unjustly arrested. His initial death sentence was commuted to hard labor. This was a dark chapter for science, where political interference overshadowed genuine scientific inquiry. Can you imagine dedicating your life to research, only to be punished for it?Tragic Death and the Siege of LeningradVavilov’s imprisonment took a toll on his health, leading to his death in 1943 under dire conditions. The irony is striking: the man who dedicated his life to preserving seeds died from starvation. During the 872-day siege of Leningrad, the Vavilov Institute faced immense challenges in protecting its vast seed bank. With seeds from 187,000 plant varieties, including 40,000 food crops, the institute had to safeguard this invaluable collection from plunder and freezing temperatures.Despite their own hunger, the scientists at the institute refused to eat from the seed collection. They planted seeds in a small plot outside the city, tilling the land by hand. Their sacrifice ensured the preservation of these seeds for future generations. When the siege ended, the allies had opened the door - sitting on bags of rice and varieties of beans, nine scientists had died from starvation while guarding the seed bank. Their dedication to the importance of seeds to future generations is a powerful reminder of the lengths to which individuals will go to protect knowledge and resources.Vavilov's LegacyVavilov’s tragic end did not overshadow his contributions to science. In the 1960s, he was rehabilitated and recognized as a hero of Soviet science. His work in plant genetic diversity and seed banks remains celebrated, leaving a lasting legacy in agricultural science and genetic conservation. Today, his principles guide efforts to build community seed banks, particularly in remote Australian Aboriginal communities.By preserving unique plant genetic resources, we can safeguard the future of agriculture in the face of climate change. Vavilov’s approach to collecting plant materials in their original habitats is a guiding principle for these initiatives. His legacy fuels the creation of seed bank networks that not only protect rare plant genetics but also empower communities to engage in sustainable practices.Nikolai Vavilov’s life is a testament to the power of dedication and the importance of preserving genetic diversity. His story reminds us that the fight for sustainable agriculture is not just about science; it’s about humanity. As we face global challenges in food security, Vavilov’s work continues to inspire and guide us toward a more sustainable future.Nikolai Vavilov's legacy in the world of plant genetics and seed conservation offers valuable lessons in resilience, dedication, and the importance of preserving biodiversity amid political, social and environmental upheavals. As we face global challenges like climate change, Vavilov's work remains more relevant than ever.

4 Minutes Read

May 14, 2025

The Seed of Change: Discovering Vandana Shiva's Impact on Agriculture and Biodiversity