Back in 2010 I was sitting at a table with a group of organic seed farmers after just having listened to Percy Schmeiser give a talk about his experiences with Monsanto. Without resources or financial help, 70-year-old Percy Schmeiser engaged in a modern day David vs. Goliath endeavor and created a ray of hope among farmers all around the world. Nearly a decade earlier I had spent a year in India with my mentor and friend Dr.Vandana Shiva, visiting the devastated communities and families who were impacted by the wave of farmer suicides caused by Monsanto GMO technology having failed small farmers. And here they were again, the beast was right in my backyard with their acquisition of Seminis seeds.

" Corporations are nothing but a glorified parasite leaching blood out of our society. For a businessman, it is the profit that matters and not cultural values. However, are we going to take a stand against those Goliath who ruins our roots? Or will we just stand and watch? "

Percy Schmeiser

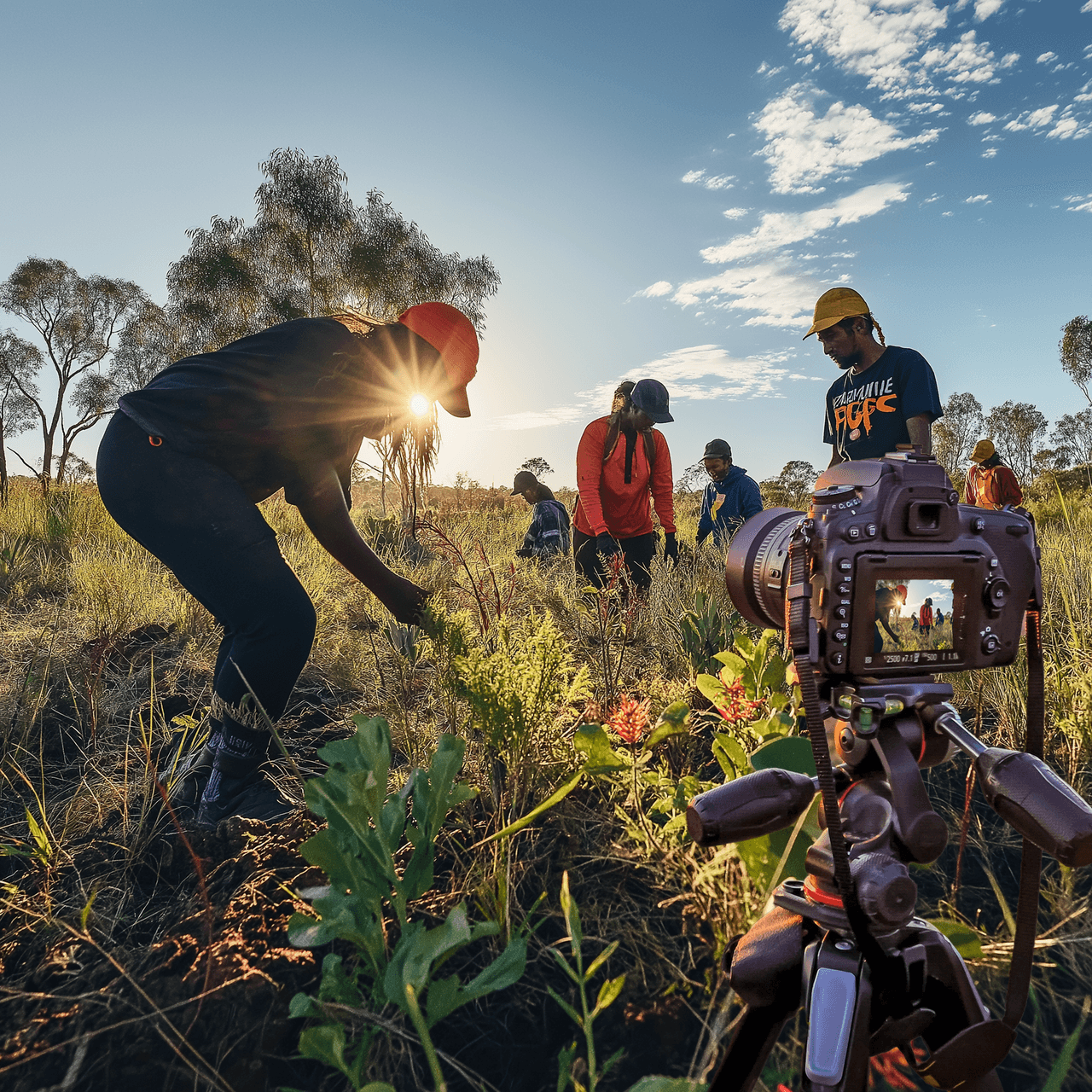

Working as part of a group of organic seed famers, my company, Edible Gardens, operated an heirloom seed grow operation in the fertile Santa Barbara hinterland. All of us in OSGATA recognized we were at risk of losing everything if Monsanto ever targeted one of our operations.

At that table we decided to spearhead a lawsuit against biotech giant Monsanto to challenge the company’s patents on genetically modified seed...

The lawsuit was filed on behalf of the group of farmers, including my company Edible Gardens, by the Public Patent Foundation . The suit was filed in federal district court in Manhattan.

“St. Louis, Mo.-based Monsanto has sued farmers for patent infringement in cases where the company’s genetically modified seed has landed on the farmers’ property,” Dan Ravicher, lead attorney in the case and the Public Patent Foundations’s executive director, said in a statement. “It seems quite perverse that a farmer contaminated by GM seed could be accused of patent infringement, but Monsanto has made such accusations before and is notorious for having sued hundreds of farmers for patent infringement.”

The lawsuit asks the court to declare that if farmers are ever affected by Monsanto’s modified seed, they cannot be accused of or sued for patent infringement.

Organic farmers have been angered by the use of genetically modified seed because it damages their organic seed when it spreads. According to the statement, organic canola seed has become virtually extinct since Monsanto introduced genetically modified canola seed, and “organic corn, soybeans, cotton, sugar beets and alfalfa now face the same fate.”

“Santa Barbara is a community with a rich agricultural heritage and an abundance of organic farmers,” said William Martin, president of Edible Gardens and a plaintiff in the lawsuit. “Once a natural seed variety is contaminated, there is no turning back — the genetics are altered forever. Under the current patent laws, these seeds and the crops are considered the property of Monsanto, which has a vested interest in eliminating natural, open-pollinated varieties.

“We are on the verge of losing, in one generation, much of the agricultural diversity humankind created in the last 10,000 years. Our future will depend on how well we steward our precious resource of natural seeds and pass them on to future generations.”

The lawsuit comes on the heels of a recent USDA decision to deregulate genetically modified alfalfa, despite court rulings against the planting of these crops.

It was standing room only as family farmers from around North America filled Federal Court Judge Naomi Buchwald's courtroom in Manhattan on Tuesday, January 31. The topic was the landmark organic community lawsuit OSGATA et al v. Monsanto and the oral argument Monsanto's pre-trial motion to dismiss which it filed last July. Plaintiffs from at least 21 States and Provinces were in the courtroom including Oregon, California, New Mexico, Colorado, Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota, Saskatchewan, Missouri, Iowa, Ohio, Florida, North Carolina, Virginia, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, New York, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Vermont and Maine.

"We were very pleased that the court granted our request to have oral argument regarding Monsanto's motion to dismiss our case today," said Daniel Ravicher of the Public Patent Foundation, lead lawyer for the Plaintiffs. "The judge graciously permitted both parties to raise all the points they wished in a session that lasted over an hour. While Monsanto's attorney attempted to portray the risk organic farmers face from being contaminated and then accused of patent infringement as hypothetical and abstract, we rebutted those arguments with the concrete proof of the harm being suffered by our clients in their attempts to avoid such accusations. The judge indicated she will issue her ruling within two months. We expect she will deny the motion and the case will then proceed forward. If she should happen to grant the motion, we will most likely appeal to the Court of Appeals who will review her decision without deference."

After the conclusion of the courtroom oral argument, the plaintiff farmers and their legal team from the Public Patent Foundation provided details and comments on the courtroom proceedings, to supporters at the Citizens' Assembly.

The large group of 83 Plaintiffs in OSGATA v. Monsanto is comprised of individual family farmers, independent seed companies and agricultural organizations. The Plaintiffs are not seeking any monetary compensation. Instead, the farmers are pre-emptively suing Monsanto and seeking court protection under the Declaratory Judgment Act, from Monsanto-initiated patent infringement lawsuits.

Early on in the legal process, Monsanto was asked by lawyers for the Plaintiffs to provide a binding legal covenant not to sue. Monsanto refused this request and in doing so made clear that it would not give up its option to sue contaminated innocent family farmers who want nothing to do with Monsanto's GMO technology.

In a remarkable demonstration of solid support by American citizens for family farmers, co-plaintiff Food Democracy Now! has collected over 100,000 signatures on it's petition supporting the rights of family farmers against Monsanto. For the past 12,000 years farmers have saved the best seeds each year to increase yields and improve traits for the food we eat. In 1996, when Monsanto sold its first patented genetically modified (GMO) seed to farmers, this radically changed the idea of how farmers planted and saved seed. Less than two decades later, Monsanto's aggressive patent infringement lawsuits have created a climate of fear in rural America among farmers. It's time for that to end. Farmers should not have to live in fear because they are growing our food.

For those who want to know the legal details...

Organic Seed Growers and Trade Association's suit against Monsanto, 2012 and 2013

By: Ernest Nkansah-Dwamena, used under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0)

Published: 2014-12-30

In March 2011 the Organic Seed Growers and Trade Association and around sixty agricultural organizations (OSGATA et al. ) filed a suit against Monsanto Company and Monsanto Technology L.L.C., collectively called Monsanto. The hearings for Organic Seed Growers and Trade Association (OSGATA) et al. v. Monsanto (2012) took place at the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York in Manhattan, New York. The district court's Judge Naomi Reice Buchwald dismissed OSGATA's suit. A year later, OSGATA appealed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in Washington, D.C., and the court agreed with the District Court's 2013 decision. OSGATA appealed to the US Supreme Court in late 2013, and the Supreme Court refused to hear the case in 2014. In the OSGATA et al. v. Monsanto case, OSGATA claimed that genetically modified seeds are a threat to both human health and conventional and organic farming. OSGATA petitioned that because of this threat, twenty-three of Monsanto's patents on genetic modification processes and technologies were invalid.

Monsanto manufactures, licenses, and sells agricultural seed varieties that are genetically modified, also called transgenic seeds. To produce genetically modified crop varieties, scientists alter the variety's genetic material (DNA) by incorporating into the organisms of that variety genes and regulatory sequences that those organisms don't normally have. This process is called genetic engineering or agricultural biotechnology. Scientists modified several different crop varieties to express traits in crops such as herbicide tolerance and pest resistance. These crop varieties became commercially successful because the engineered traits protect crops yields under adverse circumstances. Some of Monsanto's most popular genetically modified varieties are called Roundup Ready. Those varieties tolerate exposure to the herbicide glyphosate, commonly called Roundup, which enables farmers to control weeds without damaging their crops.

In the early decades of the twenty-first century, Monsanto was the world's largest seed producer and controlled about 85 percent to 90 percent of the seed market for soybeans, corn, cotton, sugar beets, and canola grown in the US. Monsanto relied on patents to protect its investments in seeds, traits, and production biotechnologies, and Monsanto licensed its patents to other seed companies. Monsanto permitted farmers to use its patented seeds under a limited-use license, which allowed farmers to plant, harvest, and consume or sell patented crops in a single growing season. A limited-use license did not allow farmers to save any of the harvested crops for replanting or to supply to other farmers.

OSGATA is a coalition of farmers, seed growers' associations, seed distributors, agricultural organizations, and public advocacy groups headquartered in Washington, Maine. According to OSGATA, they represented about 300,000 individuals and 4,500 farms or growers who had no interest in genetically modified seeds and do not use or wish to possess or sell any genetically modified seeds, including those covered by Monsanto's patents. OSGATA said that even though they did not use Monsanto's seeds, their crops could become contaminated by genetically modified varieties. Inadvertent contamination may occur through seed drift or scatter, crosspollination, and during harvest or postharvest activities such as transportation, and storage. As a result, Monsanto could sue for patent infringement should Monsanto's genetically modified seeds contaminate OSGATA members' farms. OSGATA was also concerned that transgenic contamination would cause farmers to lose their organic certification from the US Department of Agriculture, located in Washington, D.C.

OSGATA preemptively sued Monsanto based on these issues. On 29 March 2011, OSGATA filed a complaint against Monsanto at the Southern District Court of New York. They sought a declaratory judgment that twenty-three of Monsanto patents were invalid, unenforceable, and not infringed under the Patent Act. OSGATA argued that Monsanto's genetically modified seeds were not safe for societal use, and were invalid under the Patent Act, which says that only technology with beneficial societal use may be patented. OSGATA argued that Monsanto's genetically modified seeds worsen people's health.

In their argument, OSGATA asserted that genetically modified crops are indistinguishable to the human eye from conventional varieties. OSGATA claimed that genetic testing, the only proactive way to detect genetically modified contamination, is expensive, and that contaminated crops must be completely destroyed. Further, OSGATA claimed that the constant threat of genetically modified seed contamination could destroy their market. In addition, they said that they had the right to do their businesses without taking expensive precautions that lessen their risk of contamination.

In April 2011, after filing the original complaint, OSGATA requested in a letter that Monsanto sign a written waiver that protected OSGATA from claims of patent infringement. Monsanto denied that request and responded that it was not their policy to exercise patent rights against farmers whose fields inadvertently contained trace amounts of patented seeds or traits. According to Monsanto, a written promise not to sue OSGATA was unnecessary because the company had no incentive to sue OSGATA. In July 2011, Monsanto filed a motion to dismiss the case for lack of subject matter jurisdiction, arguing that OSGATA had failed to allege an actual case or controversy. Subject-matter jurisdiction is the authority of a US court to hear cases of a particular type or cases relating to a specific subject matter or controversy initiated in its court.

The United States District Court for the Southern District of New York called an oral hearing in January 2012 to hear both parties' cases. Then in February 2012 judge Buchwald dismissed OSGATA's petition against Monsanto. The district court judge compared OSGATA v. Monsanto's case to MedImmune, Inc. v. Genentech, Inc., a US Supreme Court case from 2007. Buchwald considered whether, under MedImmune, Inc. v. Genentech, Inc. (2007), there was a substantial controversy between the two parties to warrant a declaratory judgment. Because Monsanto had never demanded royalty payments from OSGATA or identified any OSGATA conduct as potentially infringing on patents, the judge ruled that there was no substantial controversy. OSGATA based their argument on three types of alleged actions by Monsanto, none of which the judge considered to be a substantial controversy. First, Monsanto's alleged pattern of litigating against non-OSGATA farmers over patent rights. Second, an implicit threat in Monsanto's statement to not enforce their patent rights against farmers whose crops inadvertently acquired trace amounts of patented seeds or traits. Third, Monsanto's refusal of OSGATA's request to provide a written promise not to sue them.

The district court ruled that OSGATA did not establish a substantial controversy or case. Buchwald ruled that if Monsanto did present OSGATA with a lawsuit, OSGATA could establish a case or controversy. The judge found that OSGATA overstated their allegations about Monsanto's patent enforcement and previous lawsuits, and that the number of lawsuits Monsanto had filed represented only a small portion of farms in the US. The court also ruled that OSGATA's attempt to demand from Monsanto a written promise not to sue was an attempt to create a controversy.

In March 2012, OSGATA filed an appeal with the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in Washington, D.C., to reverse the lower court's decision. In June 2013 Judge William Curtis Bryson, Judge Timothy Belcher Dyk, and Judge Kimberly Ann Moore presided over the hearing with Attorney Daniel Ravicher and Attorney Seth Waxman representing OSGATA and Monsanto, respectively. The three judges affirmed the lower district court's dismissal. They concluded that there was no case or controversy because Monsanto had made binding assurances that it would not take legal action against farmers whose crops might inadvertently contain traces of genetically modified traits, which the court defined as less than one percent. Monsanto had agreed "not to take legal action against growers whose crops might inadvertently contain traces of Monsanto biotech genes (because, for example, some transgenic seed or pollen blew onto the grower's land)."

The judges asserted that Monsanto was legally bound by its commitment to not sue OSGATA for patent infringement through inadvertent contamination of Monsanto's seeds or traits, and that the commitment would be upheld if Monsanto changed its position. The court noted that if OSGATA or other farmers behaved outside of the limits inadvertent contamination, Monsanto's promise could not be upheld. Because OSGATA said that they would not intentionally use Monsanto's seeds, the judges ruled that OSGATA presented insufficient controversy that merited no declaratory judgment. Finally, the judges found that OSGATA's concerns about the environmental and health effects of genetically modified seeds were outside the scope of this case, which focused on patent rights.

OSGATA's final appeal against Monsanto occurred at the level of the US Supreme Court. In September 2013 OSGATA petitioned the US Supreme Court, located in Washington D.C., to hear its case against Monsanto. In January 2014 the Supreme Court did not select OSGATA's case for review.

Sources

Bartz, Diane, and Carey Gillam. "Monsanto Critics Denied U.S. Supreme Court Hearing on Seed Patents." Scientific American , January 13, 2014. http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/monsanto-critics-denied-us-supreme/ (Accessed August 6, 2014).

MedImmune Inc. v. Genentech Inc. 549 U.S. 118, 127 (2007). http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?q=MedImmune,+Inc.+v.+Genentech&hl=en&as_sdt=806&case=14388218096121279792&scilh=0 (Accessed August 19, 2014).

Organic Seed Growers and Trade Association. "OSGATA et al. v. Monsanto." List of documents. http://www.osgata.org/osgata-et-al-v-monsanto/ (Accessed August 6, 2014).

Organic Seed Growers and Trade Association v. Monsanto Company and Monsanto Technology LLC. 851 F. Supp. 2d 544 (S.D.N.Y. 2012). http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=13942448824363195966&q=Monsanto+Company+v.+Organic+Seed+Growers+and+Trade+Association+(OSGATA),+Et+al.,+(2011)&hl=en&as_sdt=806&scilh=0 (Accessed August 6, 2014).

Organic Seed Growers and Trade Association v. Monsanto Company and Monsanto Technology LLC. 718 F.3d 1350 (4th Cir. 2013), cert. denied, 134 U.S. 901 (U.S. Jan. 13, 2014). http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?q=Monsanto+Company+v.+Organic+Seed+Growers+and+Trade+Association+(OSGATA),+Et+al.,+(2011)&hl=en&as_sdt=806&case=8314236949096655850&scilh=0 (Accessed August 6, 2014).

Ravicher, Daniel B. "An overview of OSGATA, et al. v. Monsanto." In Strengthening Community Seed Systems. Proceedings of the 6th Organic Seed Growers Conference. Port Townsend, Washington, USA, 19–21 January, 2012 . Port Townsend, Washington: Organic Seed Alliance, 2012: 140–3. http://www.seedalliance.org/uploads/2012%20OSGC%20Proceedings%20FINAL.pdf (Accessed August 6, 2014).