When it comes to nursery planning for a Cultural Plant Propagation Centre, every location is a unique story, shaped by its soil, water sources, community priorities, and the unpredictable realities that emerge once you actually begin to bring all the pieces together.

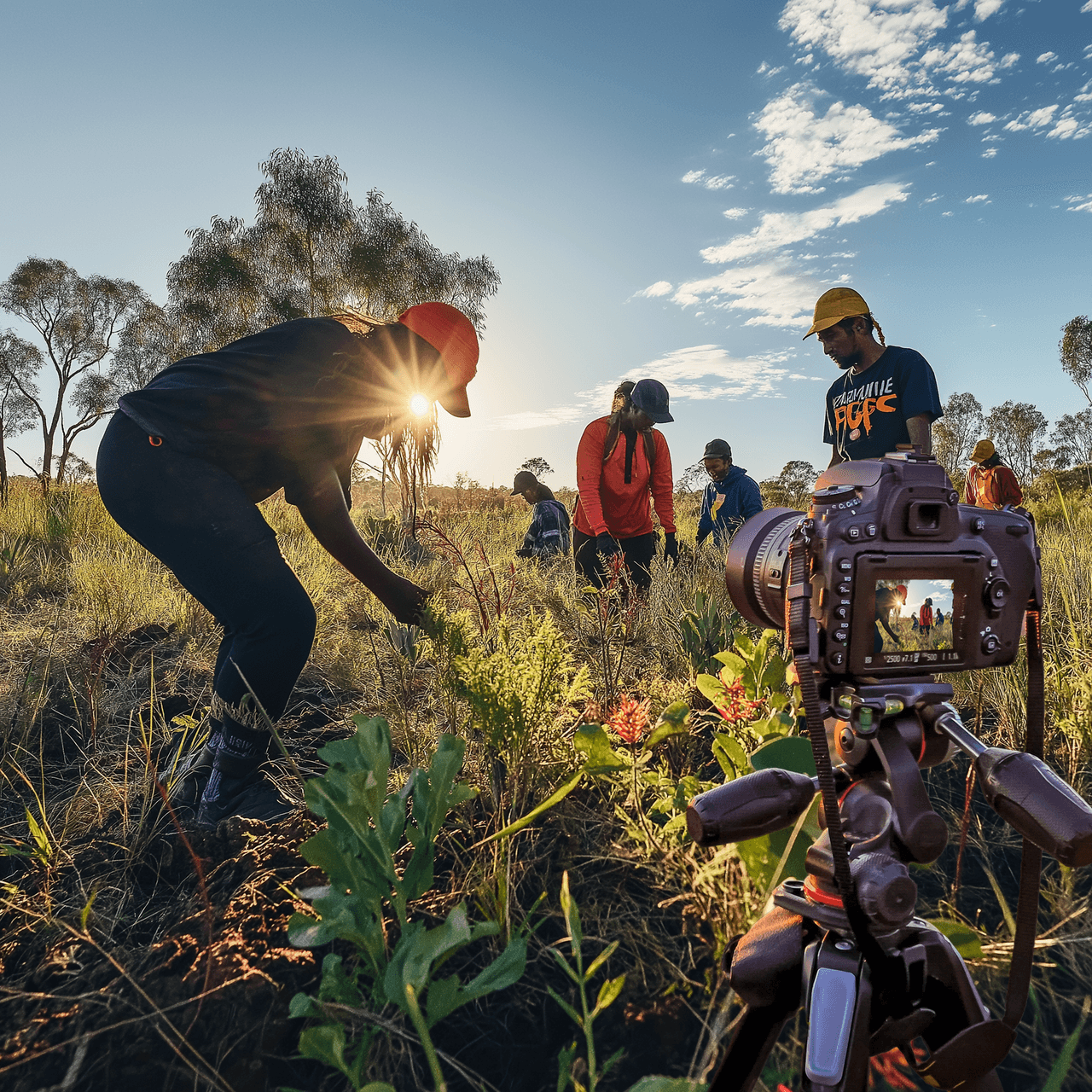

My experience over the last decade has brought me to this understanding - no matter how carefully I mapped out a budget or drew up a timeline, no matter what the parameters of the project funding said, the reality of the real situation on the ground always found a way to surprise me. Effective community engagement not only mitigates risk, it is the foundational element of developing a sustainable plant nursery project. This process of drawing on the expertise of community members, botanists, rangers and our team of nursery managers honours and reflects the amazing diversity of experience available. Each community has brought a different perspective, shaped by their land, culture, climate and needs.

It All Begins with Community Engagement

Every site begins with a community engagement. This isn’t just a box to check; it’s a fundamental process that reveals the deeper potentials of your greenhouse project. It can be the difference between long-term sustainable success, and failure. What works for one nursery—say, a focus on mine site restoration—may be irrelevant for another, where bush food and cultural plants like lemongrass or acacia are the priority. Engaging with community stakeholders, from elders to local schools and any land and sea rangers in the region, is not just best practice—it’s essential for understanding what your nursery should become.

The importance of Site Selection

Site selection is where environmental and community considerations take centre stage: this is about having reliable access to quality water. But that’s just the beginning. sunshine, community considerations, energy reliability, land availability, land council zoning, and microclimate all play crucial roles. Surprises are inevitable—sometimes a site that looks perfect on paper reveals hidden challenges, like unexpected restrictions from a land council or deeper issues within the community.

Start at a Managable Scale

One of the best pieces of advice is to start with a smaller scale nursery. This is a risk mitigation strategy, but it’s also a reality check. My first nursery in Tennant Creek, NT taught me that developing cost estimates is never as simple as it seems. Labor, outreach, infrastructure, and even small supplies add up quickly. It is also vital to factor in the costs of community engagement - cultural advice and education are often overlooked, but critically important for long-term success.

See What other Communities are Doing

Visiting other nurseries has been invaluable. Some thrive on volunteer energy, with a flexible, community-driven approach. Others run like small-scale businesses, with strict protocols and detailed work plans. Both models have their strengths, and seeing them in action has helped me refine the best practices we use at Bush Botanics. Adapting strategies from a range of nurseries leads to better outcomes, especially when combined with ongoing feedback and adaptation - see what is already working, and why.

Ultimately, building and managing a Cultural Plant Propagation Centre is about embracing unpredictability and engaging the entire community. Strategic planning, detailed cost estimation, and a willingness to learn from both mistakes and successes—these are the real foundations of a resilient and sustainable nursery project.

Begin With the End in Mind

When I first started building plant nurseries in remote communities, it was mostly about bush foods and botanicals. Having evolved this process into the ecological restoration sector, it has fundamentally changed how I approach cultural plant propagation and nursery management. The philosophy is simple, but its impact is profound: start at the outplanting site, not in the greenhouse. This means every decision—from species selection to propagation protocol—flows from the needs of the land and the people who will steward it. You can’t separate the plant from its purpose, or the nursery from its people. Knowing what and where you are going with the plants is a key distinction that will inform the entire process.

In practice, this approach turns nursery work into a living feedback loop. It’s not just about growing plants; it’s about growing the right plants, for the right place, at the right time. The starting with the end in mind approach is built on six sequential steps, each designed to ensure that every plant leaving the nursery is set up for success in its new home:

Define project objectives: Whether it’s ecological restoration, using traditional food varieties like acacias and lemongrass, or planting hardwoods for boomerangs and cultural harvest, clear goals come first.

Choose the best plant material: Seeds, root stock, cuttings, bareroot, or container seedlings—each has its place, depending on the site and purpose.

Ensure genetic diversity: Research shows that maintaining genetic diversity is crucial for resilient plant populations. This means sourcing from a broad range of donor plants and matching seed zones to outplanting sites.

Identify site limiting factors: Water, soil, temperature, winds, erosion—these can make or break outplanting success. Each site tells its own story.

Select the optimal planting window: Timing matters. While spring is traditional, autumn or even summer plantings may be best, especially with specially conditioned stock.

Pick the right tools and process: From bobcats and augers to cultivators and wheelbarrows, the method must fit both ecological and practical needs.

What surprised me most was how this approach deepened my understanding of culturally important plants. For many indigenous nurseries, the goal isn’t just ecological restoration—it’s cultural renewal. Plants like saltbush, lemon myrtle (Backhousia citriodora) and Bush tomato (Solanum centrale) aren’t just species on a list; they’re woven into traditions, livelihoods, and identities. Outplanting for these priorities adds layers of meaning and complexity that go far beyond standard nursery practice. Plus accessibility to the harvest areas is crucial.

Another lesson: genetic diversity and seed zones are worth exploring (more on this in future posts). Studies indicate that matching plant genetics to local conditions is essential, especially for long-term resilience.

Ultimately, this approach of designing the nursery based on what and where the plants are going to end up is a philosophy rooted in collaboration. It asks nursery managers to listen—to the land, to their clients, and to the community members they serve. It’s a reminder that cultural plant propagation is as much about people and place as it is about plants themselves.

Learning as You Go

If there’s one truth I’ve learned from years in nursery management, it’s this: even the best training is no guarantee of long-term success. Every season brings its own surprises. One year, a late frost might threaten young seedlings; the next, a rogue camel invasion can undo weeks of careful planning. These aren’t just inconveniences—they’re reminders that best practices must be flexible. Research shows that outplanting success depends on more than just following protocols. Soil conditions, seed quality, plant selection, and adaptability all play a role. Sometimes, despite our best efforts, we only know if we got it right after several years—and a few failures—have passed. Stay resilient!

That’s why ongoing evaluation is at the heart of effective nursery management. Bush Botanics has been working with our community partners in monitoring outplanting results for over many years now - and we are just getting started. This long feedback loop is essential. It’s not enough to see plants in the greenhouse looking healthy; true success is measured by their survival and growth in the field. Community engagement is also critical. I’ve found that regular outreach and engagement—whether through educational events, informal visits and conversations, or structured feedback—shapes our routines in unexpected ways. Our ongoing staff training evolves as we learn from both our own experiences and the wisdom of elders, instructors, land and sea rangers and community members. Our advisory services and hands-on support empowers teams to respond to new challenges, and provides time and support for experimentation into the overall project schedule. This is an important part of the process.

I’ve learned to see the planning process as ongoing. It’s not a one-time event, but a cycle of revisiting the vision, assessing progress, trying new things and adjusting to new realities. Sometimes, the most valuable insights come from unexpected places—a elder’s observation, student feedback, or the results of a small pilot project. These moments remind me that nursery management is as much about listening and learning as it is about growing plants.

In the end, the path to growing a successful cultural plant project is rarely straightforward. It’s shaped by the land, the community, and the willingness to adapt. Our Nursery Management Course can provide a foundation, but it’s our working together as a collective experience, building capacity and resilience, and a lifelong commitment to best practices that truly sustain a native plant nursery. The journey is long, sometimes uncertain, but always rooted in collaboration, growth and community aspirations.

Running a successful on-country cultural plant nursery—particularly in remote communities—demands creative teamwork, localized strategies, and the humility to adapt and learn.

The rewards?

Plants that heal ecosystems, cultural revitalization, and communities coming together in learning and celebration.

If the Bush Botanics team can help you plan, fund, build or manage your native plant nursery, please contact us at william @ bushbotanics.com.